9 things you should know about Langston Hughes

Famed writer and one-time Lawrence resident Langston Hughes, born in Joplin, Mo., is celebrated throughout the University of Kansas and the city. To help us celebrate his birthday and kick off Black History Month, we spoke to professors across campus to tell us what we should know about Hughes’ significant and broad career and the lasting impact his work had on American culture … in a nutshell.

He grew up in Lawrence, Kansas

Though born in Missouri, Langston Hughes moved to Lawrence to live with his grandmother Mary Langston. Hughes primarily lived with his grandmother during his early childhood while his mother moved about seeking jobs. “Hughes spent his formative years in Lawrence. He learned many of his values from his grandmother, which are revealed in his various forms of writing,” said Edgar Tidwell, professor of English. A number of autobiographical moments from his time in Lawrence appear especially in Hughes’s novel “Not Without Laughter,” Tidwell said.

He was a major leader of the Harlem Renaissance

“When you think of the Harlem Renaissance, people often think of that as the 1920s in Harlem, New York City, and that’s natural; that’s where it started,” said Evans who has been teaching Reading and Writing the Harlem Renaissance (ENGL 105) for about five years. Hughes himself defined the Harlem Renaissance in this narrow sense. However, “in 1925, Alain Locke in his introduction to an anthology called ‘The New Negro’, predicted an ongoing kind of renaissance of black literature and the arts that he envisioned as having no end but as continuously evolving,” Evans said. “Ironically, Hughes proves Dr. Locke right because he and Zora Neale Hurston both had long careers that extended far beyond the 1920s in Harlem.”

He was a poet of the people

“His life’s work was about bringing people together socially, politically and artistically,” said Shawn Alexander, director of the Langston Hughes Center at KU and associate professor of African and African-American studies. “At the same time, in his attempts to bring people together he challenged the nation to live up to its ideals, as seen in two of his most famous poems, ‘I, too, sing America’ and ‘Montage of a Dream Deferred.’” He was also one of the first artists to write jazz poetry. “His first volume of poetry is called ‘The Weary Blues’ in 1926. Here he is integrating jazz and blues rhythms, subjects, themes into poetry. He is experimenting with this,” Evans said.

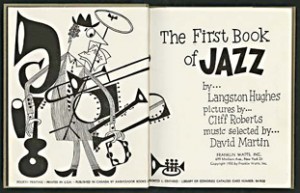

He was more than just a poet; he was a writer in almost any genre you can think of

“Hughes is known mainly as a poet but he wrote in many forms and genres, including poetry, short story, drama, the novel, autobiography, journalistic prose, song lyrics and history,” Alexander said. “For instance, in 1962 he published the first comprehensive history of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, entitled, ‘Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP.’” Throughout his career, Hughes wrote 16 collections of poetry, 12 novels and short story collections, 11 major plays, eight books for children, seven works of non-fiction, and numerous essays. “A very prolific writer in almost any genre you can think of. And his career of course, spanned decades. His career ended when he died in 1967. He was active until the last,” Evans said.

He was rebellious, breaking from the black literary establishment

“[Hughes’s> 1926 essay ‘The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain’ turned out to be something of a manifesto for the young black American writers and artists. And in this Hughes articulates for the first time a kind of racial consciousness and cultural nationalism. In other words Hughes is breaking with the establishment here in that he is asking the younger writers and artists to take pride in their blackness and their black heritage. And to make that an informing source for their art,” Evans said. “Hughes is, above all, what you might call a poet of the people in that he writes his poetry and fiction in a way that makes it accessible to just about everybody. You don’t have to have a college degree; you don’t have to have a background in Greek mythology to get what he’s going for. The themes he’s dealing with are the themes of every day black American life. I would say this is his lasting contribution in that he helped to create an environment that influenced two or three generations of writers.”

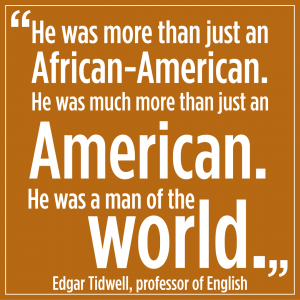

He was a world traveler

“He was more than just an African American. He was much more than an American. He was a man of the world,” Tidwell said. “A lot of people are not aware of or tend not to pay much attention to the fact that Langston Hughes was a world traveler.” His autobiographies “The Big Sea” (1940) and “I Wonder as I Wander” (1956) are admirable records of his travels throughout the United States, Europe, Africa, Russia and East Asia. He embraced the international flavor of people and their spirit of community, Tidwell said. People naturally gravitated to his warm personality, and it was said he never met a stranger.

He had a complicated relationship with his mother

“His mother was largely in and out of his life,” Tidwell said. “But she was a very complex woman.” Tidwell co-edited the book “My Dear Boy: Carrie Hughes’s Letters to Langston Hughes, 1926-1938,” which explores Hughes’ relationship with his mother through letters she sent to him during the last years of her life. While working on the book, Tidwell said he “began to learn how truly complicated Hughes’ family relationships were. It was an opportunity to see what life was like for them through the eyes of his mother. He didn’t always respond to his mother by return mail; instead, he often used his writing to take up themes that appeared in her correspondence to him.”

He worked with the father of Black History

“A brief but often neglected connection occurred when Hughes came back to the U.S. from a tour abroad. He stayed in Washington, D.C., and spent some time working for historian Dr. Carter G. Woodson,” Tidwell said.

Hughes helped Woodson catalog new and noteworthy experiences and achievements of African Americans. These achievements were celebrated in Negro History Week, which Dr. Woodson inaugurated in February 1926 between the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. In 1976 the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History (ASALH) and President Gerald Ford expanded the commemoration to the entire month. For his own pioneering scholarship, Dr. Woodson earned the designation of “the father of Black History.”

His legacy lives on at KU

“Hughes’ legacy lives in numerous ways at KU, but the most obvious example is with the Langston Hughes Center,” Alexander said. As part of the Department African and African-American Studies, the Langston Hughes Center (LHC) serves as an academic research and educational center that builds upon the legacy and insight of Langston Hughes. It coordinates and develops teaching, research and outreach activities in African-American Studies, and the study of race and culture in American society at KU and throughout the Midwest. Since the LHC’s revival in 2008 it has held four major symposiums and sponsored nearly 80 academic talks and programs. KU has also sponsored the Langston Hughes Visiting Professorship since 1977. This program attracts prominent ethnic minority scholars to the campus in a broad range of disciplines. The Langston Hughes Professor teaches two courses a semester and delivers a campus-wide symposium. Additionally, several past recipients are now tenured faculty members at KU.

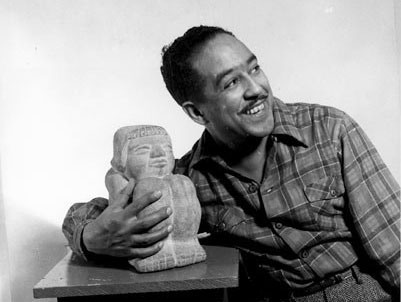

Cover photo courtesy of the Langston Hughes Center.