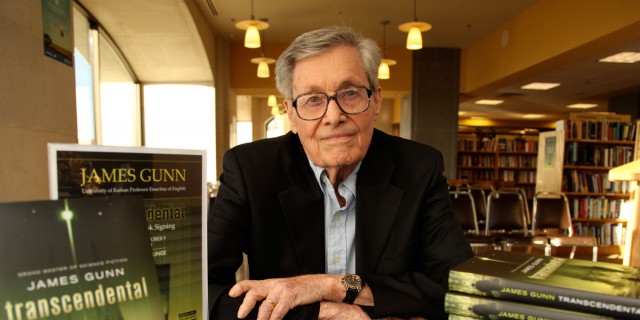

James Gunn thanks KU for lifetime of opportunity with gifts that support legacy of creative output

I can’t remember when KU wasn’t a part of my life. Officially, it began when my brother, Richard, enrolled as a junior in 1939, having combined his last two years of high school and his first two years of college in three high-school years in what was known as the “New Plan.” He kept combining—his senior year as a pre-med student with his first year of medical school, and then finished up his medical degree (with the help of the U.S. Army) in two and a half years during World War II.

I enrolled at KU in 1942 as a junior as well, having attended junior college in each of the Kansas Cities (my parents, who never attended high school but were well-informed, self-educated people, could not afford university expenses for both sons on a printer’s wages), and as a grant from the U.S. Navy to defer my service for a year after I volunteered for the Navy Air Corps. And then, after the war, I returned to finish my journalism degree, get married, do some graduate work in playwriting, and start a writing career in 1948. I kept returning, coming back in the summer of 1949 to begin work on a master’s degree in English (and to write my thesis on science fiction and get a good part of it published in a pulp magazine). And then, after a brief career as an editor and a longer one as a freelance fiction writer, I moved my growing family back to Lawrence in 1955 and was invited into one affiliation with KU after another—first as an assistant instructor of English, then as the managing editor of alumni publications, then a feature writer for the university, and the following year as Administrative Assistant to the Chancellor for University Relations. I survived the turbulent ’60s in that position, working first for Franklin Murphy and then Clarke Wescoe, until I made a decision on my own, to resign and join the English Department as a full-time instructor if the department would have me. Fatefully, Prof. George Worth, chair of the department, when he came to tell me that the department had approved my request, added that some of the younger members of the faculty hoped I would be willing to teach a course in science fiction.

It was that kind of reception that led to 23 years of my life spent teaching fiction writing and science fiction and trying to put to use the good will of the department to “let Jim Gunn teach whatever he wants to teach.” Along the way I was allowed to create a Center for the Study of Science Fiction to provide a focus for the various projects I was working on, taught a marvelous group of students, some of whom came to KU for the express purpose of studying science fiction, and saw them go on to careers in teaching and award-winning writing. Even after retirement in 1993, I continued working in the summer with the writers workshop I had created and the two-week intensive program in science-fiction literature, originally for teachers.

KU not only changed my life; it became my life. I met my late wife in the journalism school here and formed friendships that lasted for a lifetime. I had two sons who attended KU for undergraduate and graduate study, one of whom, Christopher, died too soon. It seemed natural and appropriate to honor his memory with scholarships in sociology and English. The Center for the Study of Science Ficiton had been named for my parents after my brother contributed an endowment in our father’s memory and left half of his estate to the center and the other half to a lecture fund for the English department. Two wonderful people, both former students, have taken over the science-fiction work and the center, Chris McKitterick and Kij Johnson.

One thing that I’ve always thought would enhance the stature and accomplishments of the Center for the Study of Science Fiction was a named professorship. With the support of the English department, the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences, and the University, I approached several of the most successful and famous writers in the science-fiction field. Alas, they always had other commitments. So it seemed natural and appropriate for me to leave a provision in my estate for a professorship in science fiction, a field that I have always felt, even in the early days when one professor called it “at best sub-literary,” had great promise as a medium of literature and of ideas and of a different way of considering the human condition, and, at its best, as the quintessential interdisciplinary field, a bridge between the humanities and the sciences. With the help of the KU Endowment Association and its program for deferred giving, in time there will be a James E. and Jane F. Gunn Professor of Science Fiction.