Why Aric’s a Hawk to Watch:

Russian spies. Chemical weapons attacks. Drug lords, drones, conspiracy and war crimes. A day at ‘the office’ is anything but ordinary for Aric Toler. As the director of research and training at Bellingcat, an independent international collective of researchers and citizen journalists, Aric and his meticulous team of cyber experts are following digital breadcrumbs to uncover misinformation, expose corruption, and shine a light on global injustices.

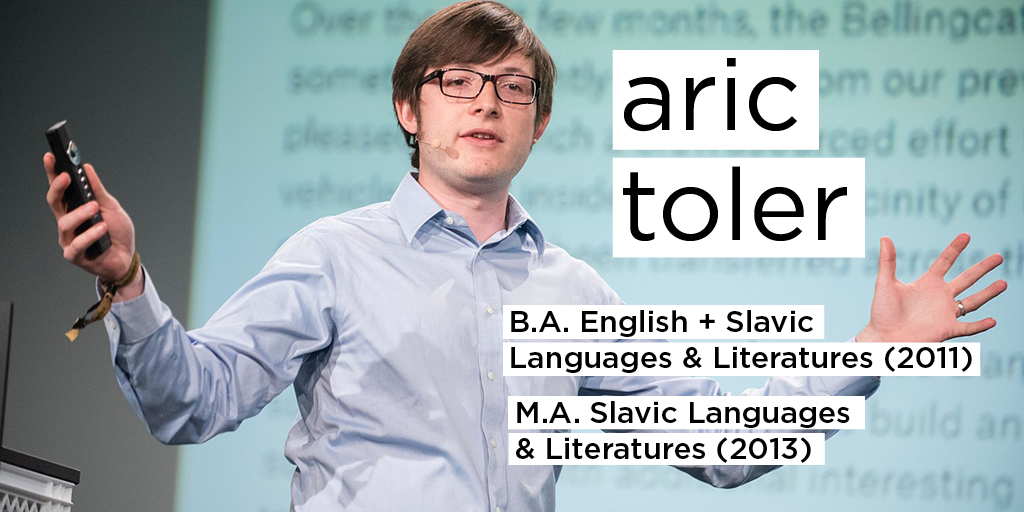

Founded in 2014 by British journalist Eliot Higgins, Bellingcat has made international headlines for its investigations into explosive recent events — the storming of the U.S. Capitol, the murder of Saudi Arabian dissident Jamal Khashoggi, and the poisoning of former Russian officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter, to name just a few. What started as volunteer work for Aric soon turned into a full-time job after his dig for Russian social media activity helped the organization identify a missile launcher responsible for shooting down Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over eastern Ukraine. And with a background in English and Slavic languages and literatures at KU, Aric fit the bill for what is perhaps the key qualification needed to land a position with Bellingcat — an ability to quickly process dense, complex information (and lots of it).

Around-the-clock data analysis, fact-checking, and online deep-dives into bad actors can make for a fast-paced work schedule. But when you truly love what you do, there’s rarely a dull moment. “It sounds grim but I don’t know how much I ever clock out,” Aric tells us. “But that’s mostly a good thing… My ‘hobby’ before starting this job was more or less spending way too much time on the Russian-language corners of the internet, and that’s what I still do.”

With a résumé full of open-source intelligence missions and detailed takedowns of corrupt power structures, we wondered what’s next for the digital investigator. “Hopefully doing more or less what I am now,” he says of his ten-year plan. “Things change so quick and often with this work that it doesn’t ever really get boring.”

Tell us in a couple of sentences what you do for a living:

As the director of research and training at Bellingcat, I spend about half of my time doing research on topics with digital open source information, such as social media and satellite imagery. The other half is spent teaching others, usually journalists and NGO researchers, how to conduct these types of investigations themselves for their work.

How did you end up doing what you do? What drew you to Bellingcat?

I started out by volunteering doing research in my spare time after the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 (MH17) over eastern Ukraine — the one that was shot down, not the one that disappeared over the ocean. I was looking for witness accounts for locals in eastern Ukraine talking about what they saw happen before and after the downing on local social networks, as Russia has its own equivalents for Facebook and other social networks. I was finding some interesting stuff, and volunteered with Bellingcat, which had just been started that same month in 2014. From there I kept digging into Russian-language social media activity on the day of the downing, which led to a report we eventually published identifying the exact Russian missile launcher that was used to down the passenger plane, and then to start working full-time as a researcher and trainer for Bellingcat in 2015 once we received a grant.

What’s the most rewarding part of your work? What are some of the most memorable projects you’ve worked on?

Digging into and uncovering Russian spy operations is good for the headlines and my CV, but being able to run training workshops for and cooperate with the Russian journalists that I was reading and almost mythologizing when I was first learning Russian as an undergrad is pretty wild. I would read their blogs back in like 2009, 2010, and watch them be arrested in protests in 2011, and then five or six years later I’m talking to the same people in my very badly-accented Russian about how to analyze satellite maps and dig through social media.

What’s your best career pro-tip?

It will vary wildly depending on your field, but most broadly I’d say to try and find some niche that you are good at and have a lot of organic interest in, and see if you can turn that into work. I got lucky on this, but especially if you get a humanities degree, your career path probably is not going to be entirely linear compared to more obvious professional-track degrees like engineering and business.

What’s your lowest career moment and how did you pick yourself up and move on?

I haven’t had too many roadbumps thankfully, but I wasn’t able to find any jobs that directly correlated to my degree either when I finished my undergrad work in 2011 or my masters in 2013. Things are a bit different now with far more remote work, but there aren’t many jobs in the US outside of New York and DC where you can use Russian much, so I had to sort of make my own new job out of it with the training and research elements.

What do you know now that you wish you could tell your 18-year-old self?

Probably nothing related to education and career choices, as there would probably be a bit of a butterfly effect that ends up sending me to some bad, dead-end job. Maybe: find a way to take out fewer student loans.

How did your KU degree prepare you for your current job?

Doing my English BA and focusing on Russian literature for my master’s help a ton with how I think about and process data, especially for complex tasks and events. A lot of people assume that having a more hard science or math background is what would help you most to be able to gather and synthesize lots of data points, but, having been a failed physics major before I jumped ship to the humanities, I find that knowing how to read and understand literature is way more applicable. When I do work researching things like Russian spies moving around the world and looking through their phone and social media records, it’s not so much processing numbers and figures as it is reading lots of texts, which is what a degree in literature prepares you to do better than anything.

What do you do after you’ve clocked out?

It sounds grim but I don’t know how much I ever clock out, but that’s mostly a good thing — my “hobby” before starting this job was more or less spending way too much time on the Russian-language corners of the internet, and that’s what I still do.

Where do you hope to be in 10 years?

Hopefully doing more or less what I am now — things change so quick and often with this work that it doesn’t ever really get boring.

Meet more of our Hawks to Watch. For more information, visit the Department of English and the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Languages & Literatures at the University of Kansas. See more from Bellingcat here.

Hawks to Watch are disrupters. They’re poised for greatness, inspiring their colleagues and excelling in their professions. Basically, they’re killing it. Having recently graduated, they are just starting to leave their mark and we can’t wait to see how their story unfolds. These Jayhawks span all industries including business, non-profits, tech, healthcare, media, law and the arts.